On September 11, 2001, Françoise Mouly, artistic director of New Yorker, was at her home in SoHo when she heard about the first plane hitting the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. After her and her husband, the well-known cartoonist Art Spiegelman (creator of mouse), picked up their two young children from school and the family was safe, she went straight to the magazine’s headquarters. David Remnick, the editor-in-chief, had called him to do a special issue.

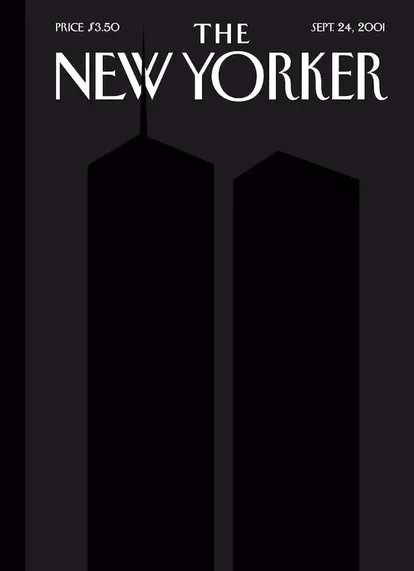

This cover, depicting the silhouettes of the Twin Towers against a dark background, is part of journalism history, as well as one of the most famous images ever published by The New Yorker: a perfect combination of design, subtlety and timing that changed the tone of the magazine. Without using images or words, Mouly knew how to convey what millions of people felt on that fateful day. How to say what could not be said. “The idea of going to the office and even thinking about looking for an image seemed embarrassing. In a conversation with my husband, he suggested silhouettes. So when I drew the silhouette black on black, I realized that, oh, it’s a way of saying that no image exists and it’s an anti-image while still being an image. It’s so escapist, subtle and you can’t put it into words,” she tells EL PAÍS.

Mouly is a tall woman with blue eyes. Her hair is short and curly, held back by the close-up glasses she wears, and her fingers are covered in rings. One of them is a large eye that follows the conversation from the index finger, as if looking through a keyhole. She was born in Paris 66 years ago but has lived in New York for more than half her life and alternates between her work at the magazine and her role as editorial director of children’s comics publisher Toon Books. . Between 1980 and 1991, together with Spiegelman, she edited the comics anthology magazine Raw, a cult publication that marked an important milestone for the industry in New York. This summer she was in Mexico as part of the jury of a design biennial held by the company Pictoline to select the best illustrators in Latin America.

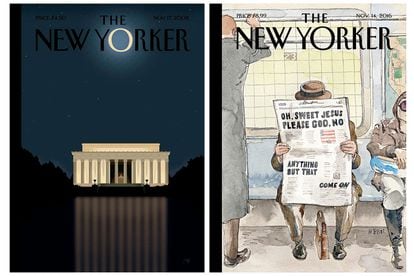

In the almost three decades she’s been on the cover of The New Yorker, Mouly has seen her country—she’s also an American citizen—and the world change hundreds of times, and she’s been there to provide the wit, insight, or sensitivity needed to tell the story with a distinctive style. She admits that the most daunting challenge is capturing the essence of a historical moment in a unique way by choosing the right illustration. “Emotions cannot be created, but we can give people an image they can identify with,” she explains. When Barack Obama won the election in 2008, the cover designed by Bob Staake featured the Lincoln Memorial in Washington – which also evokes Martin Luther King – under a large bright moon that was also the “O” in its head. “It captured everyone’s emotion because it gave a historical feeling, a new era,” she says.

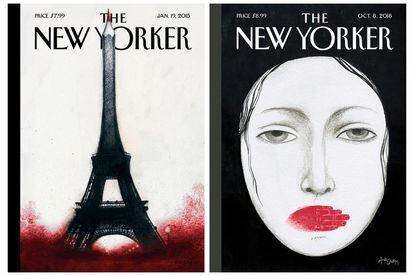

In November 2016, after Donald Trump’s victory, the cover depicted a scene on the Manhattan subway, where a man was reading a newspaper. On its pages it said, “Oh, sweet Jesus. Please God, no. Anything but that.” “We tend to give a heightened explanation to everything. But emotionally, you’re more connected to your visual sense, it’s connected to your gut […] you’re using your emotional circuits,” says Mouly, who has been able to use this nonverbal communication to discuss racism, feminism, war, abuse, and radicalization while shedding light on the darker side of American society. Illustration “gives you a channel to process pain or empathy with people,” she points out.

Mouly points out that a good cover doesn’t necessarily have to link to an article on the inside pages. “The cover is a story in itself, which should be understood in ten days or ten years”, she explains. Her office – located on the 23rd floor of One World Trade Center, where the Twin Towers once stood – is considered the most creative in the magazine’s headquarters. Similar to a gallery, hundreds of illustrations hang on the walls, showcasing the ongoing dialogue Mouly maintains with the artists to create the covers.

For many artists, being published in The New Yorker it is a reward in itself. The art director admits to throwing away “tons” of illustrations that arrive at her office every week; without a doubt, she says, the hardest part of her job. But she is a very demanding and punctual woman. So much so that a group of ladies work with him just for the cover illustrations. Things sometimes slip, though, like when the clock in a photo of Grand Central Station read 2:15 p.m., and one reader noted that it was impossible because of the amount of light coming in from the windows and the shadows being cast. on land to correspond with that time of day, or when another reader wrote to let him know that one of the characters in a beach scene had two left feet. “Readers are experts and decipher everything. Now it’s up to all of us to rise to the challenge.”

Mouly considers it important to pay attention to the work of established authors, but also to promote that of young artists beyond the United States and Europe; she is always looking for new talent and encourages young illustrators to submit their work. She is interested in showing the changes in our society, what it is like to live in this time. Since its founding in 1925, this has been one of the mainstays of publishing.

During the interview, Mouly talks about the intolerance that prevails in the United States and how this intolerance has caused the work of artists and writers (including her husband) to be censored. “Unfortunately, this is part of a very well-organized political effort by very wealthy people who have found a way to impose their beliefs,” she says. In her view of American society, she also denounces puritanism, sexism, and the demands placed on women.

Then the subject turns to 9/11, and she recalls how she first told David Remnick that the cover with two black silhouettes was her husband’s work. After all, the idea had come from a conversation with her, and she was worried that the director would not accept her suggestion, not being a well-known artist. In addition, never before had two illustrators worked on a cover together until she broke the rule (months later she gave a double credit to Rick Meyerowitz and Maira Kalman, setting a new precedent in the publication’s history).

She reflects that although the prevalence of sexism is decreasing in the 21st century, if she were a man, she would have been given more authority much earlier. However, “if I were not a woman, I would probably have been more autocratic in my exercise of power, and therefore less successful, I think.”