In the early years of this century, a Pakistani painter, traveling in a taxi in Milan, was asked by the friendly taxi driver: “Where are you from?” The passenger asked the driver to hazard a guess. “Dubai”, said the driver; to which the painter replied, “Oh come on, they could all be from Dubai.” The driver’s second guess was London and the passenger’s answer was unchanged. Finally, he told the young Italian that he was from Pakistan and that was the end of the conversation.

Cities like Dubai, London, New York are located in specific lands and parts of specific nation-states, but in a sense they are also located in South Asia, providing places and opportunities for artists, writers and other individuals. creator from the region for it. meet, exchange ideas and collaborate. Such cooperation may not otherwise be possible in the subcontinent due to visa restrictions and political tensions. Given its imperialist past, the UK is a natural/neutral haven for many professionals away from their homeland.

Diaspora, exile, migration and asylum are different forms of displacement in which a person can survive in a distant country. Remembering the past passed in the territory of ‘home’; the local clock of the abandoned lands is ticking inside the head. The search for identity has many cultural manifestations e.g language, music, faith, food and clothing.

Distance provides a wider lens to view one’s reality/roots. A number of Latin American novelists have written about the characters, places, conflicts, politics and history of their countries and the continent while living in Madrid, Paris and London. Some of the works might not be feasible if they were in Bogota, Buenos Aires, Lima, Santiago, Mexico City or Rio de Janeiro. Likewise, poets Noon Meem Rashid and Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote some of their best verse while living in London or Beirut. Several artists from our region, including AJ Shemza, SH Raza, F D’Souza and Tassadaq Suhail lived in Great Britain or Europe, but their art was a means of recalling the reality of their country of origin, so rooted in script, miniature painting, tantric forms and the religious, social and cultural narratives of the subcontinent.

Four women artists trained in British art schools formed Neuling (the newcomers) Collective in 2018 “to debate and highlight issues related to global politics and their impact on women of color.” Hailing from India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, these artists (some of them based in London) are dealing with issues of identity, tradition and heritage. Their artworks – with contemporary idioms – refer to cultural practices and folk forms.

Curated by Noor Ahmed, the work of these artists was displayed as Home Ground from August 11 to August 25 at Art Chowk, Gallery, Karachi. Paintings, textile-based installations and works on paper depicted how the idea of home could be expressed in different languages.

Perhaps the most exciting – and ambitious – inclusion were the paintings of Chudamani Clowes. Originally from Sri Lanka, Clowes “currently lives in London, where he has spent the last forty years”. She belongs to the ‘post’ generation. ‘Post’, not in terms of post-modernity or post-colonialism, post-human or post-truth, or social media posts; but postage. Before email and WhatsApp messages, people sent, waited, waited and received letters (like the old protagonist in Garcia Marquez’s novella No one writes to the Colonel who frequents the post office to ask if there is any mail).

Four female artists trained in British art schools formed the Neulinge Collective (Newcomers) in 2018 “to debate and highlight issues related to global politics and their impact on women of colour”. Hailing from India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, these artists are dealing with issues of identity, tradition and heritage.

A postman was a major presence in villages and towns before electronic mail. He brought mail, messages from loved ones. Those scraps of paper – a single page folded into an envelope to save postage – were the words (if not substitutes) of a distant father, brother, husband, son.

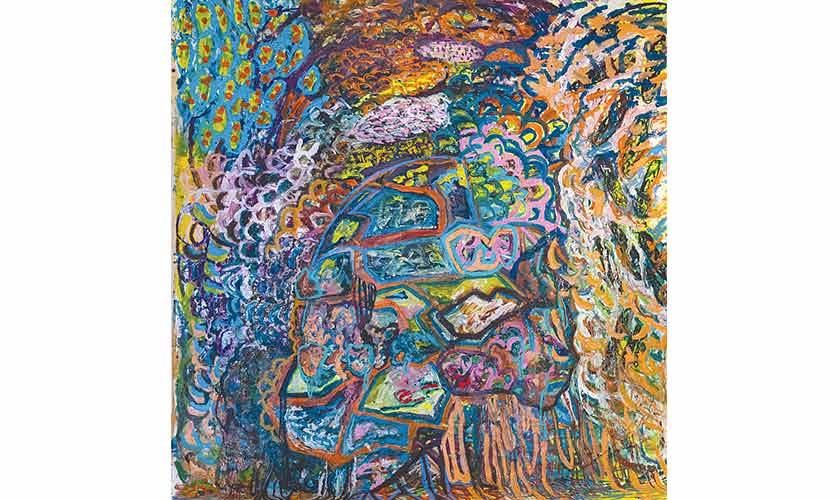

Chudamani Clowes has mastered the format of an aerogram paper to create The unexpected letter, using army tent canvas, lacquer and oil paint. With its superimposed shapes, patches and array of hues, the work becomes a transcript of an intelligible language. In fact, all writing is scribble until someone deciphers it. At the Royal College of Art, London, (where Clowes got her MA) students scribbled house letters in Hebrew, Japanese, Greek, Arabic, Bangla, Tamil that looked like the footprints of a drunken bug. However, these were legible phrases for those who could read them. Clowes constructs a text that, beyond knowing the alphabet, is about identifying the signs of love, longing and loss. Many times handwriting betrays more than what a person intended in their choice of sentences, structure of passages and editing of content.

In the age of emails and phone messages, the only handwriting left is art. Chudamani Clowes explores it to such an extent that her works become a pictorial dictionary. Her loosely drawn lines, marks and strokes convey the complexity of the narrative, along with a painterly quality that makes the work a strong visual, accessible to people of different geographies and different histories.

The connection to the past was also evident in the art of Divya Sharma, a London-based artist from India who graduated in sculpture from the Royal College of Art (2021). For Sharma “home is a state of mind”. She revives him through her textile and hanging on a thread (Form of identity, 2022). The work, with its connection to native textiles, offers layers of weaving that are more about color, shape and texture than an obvious concept. However, one cannot forget how different materials, mediums and techniques have a political, historical and gender background. The British introduced oil on canvas as the sublime and supreme medium in a country where other ways of creating images were in practice, such as gouache on paper, fresco, embroidery, wood and stone carving. Sharma’s preference for textiles is significant, as the medium remains marginalized (being non-art), especially for its association with women weavers/workers.

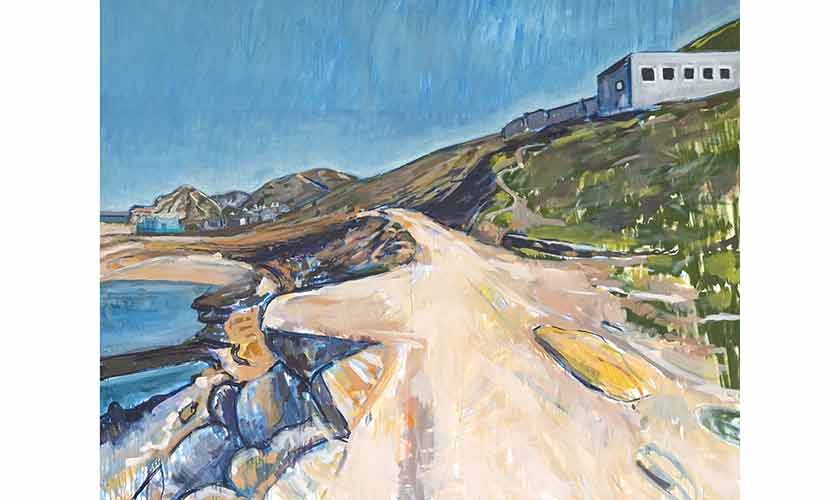

The act of recognizing and respecting forms of representation was evident in the work of Maryam Hina Hasnain. Her images of bleeding patterns in blue/green (blue prints, 2022, ink and bleach on tracing paper) suggest how one’s identity is not static or immobile or rigid (or stuck). The dotted edges of a traditional motif in large rectangles deal with the reality of tradition in a vivid, vital and energetic way, unlike the confident manner observed in Marium M Habib’s painting and chalk pastel on paper in his portrayal of the procession of Ashures and a beach house. in Karachi. Compellingly presented, these surfaces do not fall outside the expected ‘notions’ of indigeneity. A hut on the sea, as well as religious rituals to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussain (peace be upon him) become markers of identity – and attraction.

Whether you hail from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, or/and live and work in London, your creations are not limited to these changing locales. Art belongs to the hour in which the ground underfoot is neither home nor a foreign land.

Writing is an art critic based in Lahore.