Today is Christmas Day. Let us give thanks and praise the birth of a wonderfully well-researched book, Via the Round About, written by Beverly Scobie. It traces part of Scobie’s family, beginning with Joseph Arthur, the patriarch, who was “enslaved for all his formative years.”

Scobie is ambitious. She wants to tell about the “Story of determination and endurance of the Scobie family from 1819 to emancipation, the colonial era and beyond”. Although this is a bit to chew on, Scobie holds our interest throughout this wonderful journey, entertaining and enlightening us as she tells her story.

This beautifully crafted book is enhanced by well-preserved family portraits, her photographs of the area and the diverse wealth of Parisian archives. In it, Scobie integrates the growth of her family with the development of Toco and the surrounding villages where she grew up.

Scobie’s family history begins with Peter Cordner who, in 1866, traveled from Tobago to the cocoa estates of Sans Souci, Toco to look for work. She says of this dangerous trip to Trinidad: “He and his associates continued to risk their lives traveling in small boats on the open sea, the only means of getting to the cocoa estates.”

Scobie then gives us a ball-by-ball account of her family’s development, their achievements and failures. She talks about the pioneering work of some of her family members (like Isaac and her father) and even the prevalence of mental illness that affected family members, especially Mary, her grandmother.

The daring adventures of her ancestors allow Scobie to display her rich literary imagination. She writes: “When Peter Cordner first arrived, the region was still largely virgin forest, sparsely populated and isolated from the rest of Trinidad. The outlines of small enclaves were barely visible in areas where the forests had been cleared. There were no lights, so in the evening it became black and silent, except for the occasional flame of a burning torch. There were no roads and the workers walked for miles, most of the time barefoot, through densely wooded forests on dirt paths made by the foot of the First People.”

Scobie’s description of village funeral rituals is one of the most fascinating aspects of her story—the preparation of the corpse for burial, the wake scene that included limbo and bongo dancing, the prayers that were said, and the fading rituals. . These stirred my memories. When my father died in 1954, all his children and close cousins walked over his corpse three times while it lay in our living room.

Scobie’s memories of those innocent days of yore, when adults and children looked forward to moonlit nights, are also memorable: “As silly as that sounds, catching candleflies in a glass bottle and pretending it was a The lamp was really fun for kids back then. But they made sure to avoid any larger than usual candle flight, convinced it might be a Soucouyant. This was especially so after listening to the stories of adults telling tales rooted in the folklore and legends of the islands. The stories of Papa Bois, the old man of the forest who protected animals from hunters; Soucouyant, the old lady of the vampire family who would suck your blood while you slept; La Diablesse, the spirit of the unrighteous woman whose alluring dress hid a cloven hoof; and Duenne, the infant who died without the benefit of baptism. These and a host of other terrifying creatures lived among the villagers, unseen.”

She also describes the local delicacies she ate, the games the children played and all those intangibles that made those early days so special. The visual beauty of the matapal tree, the luxurious nature of the homemade tool and the bene balls make the reader want to grab and eat them off the pages.

One would be remiss if she did not speak of the central role that the Seventh-day Adventist religion played in her family’s life and the discipline it imposed upon them. She says: “My parents weren’t rich, but we didn’t lack for anything. My father’s faith was the foundation upon which his life was built. This taught him to be disciplined and hardworking. The strict routine practiced in our home when I was growing up was my father’s letter of interpretation of the law of religious doctrine espoused by the Seventh-day Adventist denomination.”

In 1947, Melville and Frances Herskovits, famous anthropologists from Northeastern University in Chicago wrote a book, Trinidad Village, which won many accolades. Well versed in the study of black life, they wrote about Africans in Toco. Harold E Davis, in a wonderful review in the Boletín Bibliográfico de Antropología Americana, praised them for using “a mature methodology based on clearly defined theoretical concepts, for this New World black community. Particularly noticeable is the clarity of their theoretical concepts. As a result, this study of Toco’s black village culture…is of unusual value to both the cultural anthropologist and the historian of New World cultures.”

Scobie’s book may lack the use of theoretical concepts, but it tells a story that is worthy of any anthropologist, historian, or casual reader who is curious about our past.

Via the Round About is no ordinary book. There is a beauty and innocence that is especially welcome at a time when there is so much brutality on our island and our people are unable to appreciate their beauty and truth.

Congratulations are therefore due to Beverly Scobie for showing us this wonderful part of our island and our people at a time when it is so needed.

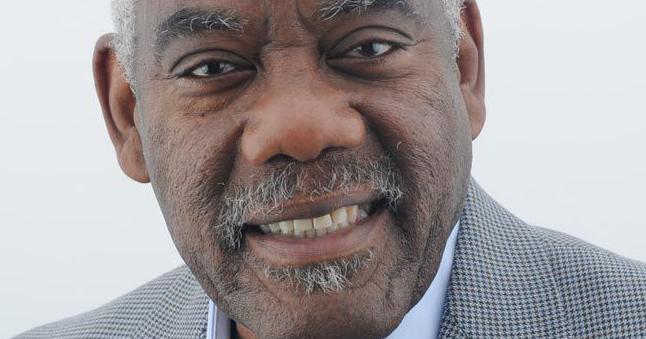

— Prof Cudjoe’s email address is [email protected]. He can be reached @ProfessorCudjoe.