India’s mom-and-pop investors are facing testing times. During a pandemic-era surge in the stock market, millions poured their savings into stocks, relying on advice from unauthorized financial advisers and social media “gurus” to help identify the next big ticket.

But a recent slide in share values has highlighted the dangers of India’s lax capital market regulations. Many amateur retail investors, especially young people, sought to make a quick buck by consulting informal groups on platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram. Recourse for lost investments is limited: in India, fines for everything from insider trading to wire fraud are a fraction of those imposed in some Western countries.

India’s regulators are now cracking down on online scams. The Securities and Exchange Board of India recently urged investors to remain vigilant against so-called “pump and dump” schemes – a type of securities fraud that involves artificially inflating prices – and not to rely on advice for shares from unverified online services.

It is an increasingly charged topic around the world. Securities regulators from Spain to Australia are considering ways to enforce restrictions against social media influencers. Earlier this year, SEBI shut down a Telegram channel called “Bullrun2017” that purported to specialize in penny or small-cap stocks. The administrators of the group bought shares of small companies, recommended them to around 50,000 of their subscribers and then sold them for a profit, according to a SEBI order.

In March, the regulator raided premises linked to seven individuals and a company that ran nine Telegram channels with more than five million subscribers. They used a similar strategy of inflating prices and then selling stocks at high levels. Telegram declined to comment.

“Most of these paid services are not good,” said Aditya Trivedi, 25, who runs a popular Telegram group that offers free advice on trading calls. “They regularly post fake pictures of their earnings to stimulate greed. A little boy is touched by the hope that they too will make money.”

Trivedi, who has more than 30,000 followers and learned trading from Twitter, said companies often reach out to influencers like him for paid advertising to boost their stock value. He said he refused such requests.

The gaps continue

The broad challenges of social media policing don’t help. In April, Twitter was suddenly flooded with recommendations from several verified handles to invest in Supreme Engineering Ltd stock. – a Mumbai-based manufacturer of specialty alloys and wire products – after securing a government contract. After the online promotion, the penny stock gained close to 21%.

Twitter and Supreme Engineering did not respond to requests for comment.

Implementation is often complicated in India. Unlike many Western countries, where laws protecting investors are formidable and long prison sentences are a real prospect for violators, India’s convoluted legal system hardly acts as a deterrent. Many cases drag on without resolution. The capital market regulator was given the authority to arrest securities law violators only a few years ago.

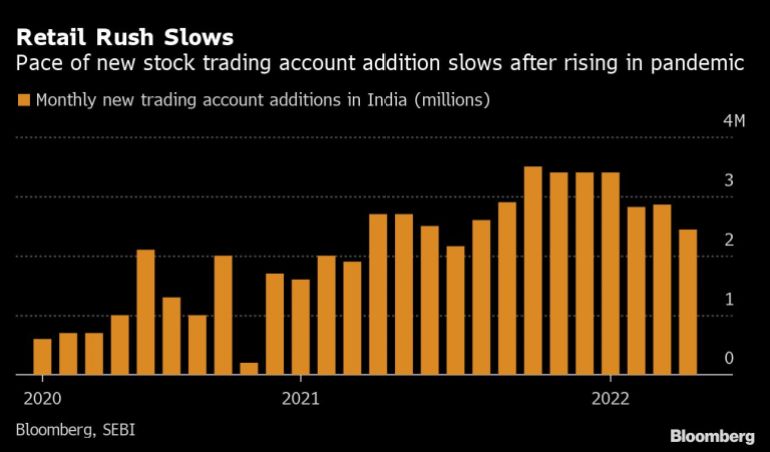

What is clear is that domestic retail investors are here to stay. India has seen a steady rise in such investors over the past five years as a stagnant real estate market and low interest rates prompted the middle class to explore capital markets. This new set of investors is now a key dampener for India’s $3.2 trillion stock market, after a slide in global indices due to rising oil prices and the Russia-Ukraine war.

The number of new e-commerce accounts opened each month has increased sixfold between 2019 and 2022, according to India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman.

But online fraud has grown along with the rise of inexperienced investors. Indian consumers were 10% more likely than the global average to experience a scam and three times more likely to follow through with a scam, according to a recent study by Microsoft Inc. The report consulted more than 16,000 Internet users in 16 countries.

Vivek Mashrani, a former banker and founder of Techno Funds Ventures Pvt Ltd, an investor education firm, said the Internet has replaced television as the medium of choice for such scams in India. “Wherever the audience’s eye is, people will use those channels directly or indirectly for their vested interests,” he said.

Many fraudsters have taken advantage of the lack of registered investment advisers in India. The country currently has about 62 million unique investors, according to the National Stock Exchange of India, compared to just 1,330 advisers. According to SEBI rules, only certified analysts are allowed to provide financial services.

But loopholes persist, especially online. In 2016, SEBI proposed to ban unregistered individuals or firms from giving investment advice through social media. However, the recommendation should still provide clear rules on whether advice can be given in an informal educational capacity, an ambiguity that many continue to exploit.

“Considering the growing influence of social media platforms on investors, SEBI is likely to make changes in its regulations to fill the loopholes,” said Sumit Agrawal, a former SEBI legal advisor. “The success of such changes will depend on how these regulations are implemented.”

SEBI did not respond to several emails and phone calls seeking comment.

Identification of traps

Kanika Arora, 34, an accountant from Mumbai, is an investor who said she fell into such a trap last year.

After subscribing to the portfolio management services offered on Telegram by Namdev Mane Trading Academy, the eponymous founder contacted him directly on the platform. “I would personally buy and sell on your account,” Mane wrote, noting that he would collect 40% of the profits and pay a one-time fee of about $60. “Please note that you cannot make money by marketing yourself.”

Within months, Arora said she had lost more than half of her 100,000 rupee (about $1,250) investment.

“Ultimately, I was guilty of trusting someone who was not a SEBI-registered portfolio manager and therefore did not take any further action,” she said, adding that a friend had recommended Mane’s services to her.

In an interview, Namdev Mane, who lives in the city of Pune, said he is an options trader and has an MBA, but was not registered with SEBI as an investment adviser. He denied wrongdoing, noting that he offers calls on Indian indices but does not offer advice on stocks.

“Market miss is not the same as fraud,” he said. “I am not forcing anyone to take my services.”

Mashrani, the former banker, said Indian regulators should increase the number of investment advisers by easing some restrictions. The NSE warned retail traders this month about reckless derivatives trading after it noticed that many online influencers were promoting complex options trading to inexperienced clients.

“More qualified people are needed to be allowed into the formal channel,” Mashrani said. “This will automatically weed out the unregulated boys.”