TheIn early July, a Twitter account was called out Zimbabwe posted a thread highlighting the popularity of country music across Africa. The posts included videos — mostly phone footage from bars and weddings — that convincingly supported the claim. A man in a cowboy hat moonwalking to Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler”; a group of women dancing happily with Kenyan star Sir Elvis covering Wagon Wheel, a 2013 hit for Darius Rucker.

These pictures of country music woven into the fabric of everyday African life elicited an almost unanimous response: surprise and delight. The start quickly garnered thousands of retweets and a flurry of amazing responses. But many across the diaspora may have felt it stirred something deeper. I have spent years tracing my love of country music through the generations and have found it to be an underappreciated thread in global black music and black British heritage.

If you’ve spent time in rural sub-Saharan Africa, one thing that might shock you is the popularity of American country music to the point where you can’t go to a bar, party or wedding without avoiding it 🧵 pic.twitter.com/gpYC7fdq78

— Zimbabwe (@RisenChow) June 30, 2022

A few years ago, the fascination around this topic might have been a passing curiosity, but the Twitter poster was smart for the times. The place is cold again. US and global streaming figures have grown by 50% in the last two years and it is the UK’s fastest growing genre on streaming platforms. Place has also become a cultural talking point as we explore the tensions between the genre’s carefully constructed image of whiteness and the diversity and complexity of its long-hidden history.

Country music has borrowed heavily from black sources since its inception in the 1920s—a pattern that continued through the decades. But efforts to remedy this have gained ground. From grassroots initiatives like the Black Opry, SoulCountry and Country Queer, to the success of country acts like Allison Russell, there’s an appetite to reimagine country and connect it to its true roots.

Why, then, does the idea of an African country still remain unexpected? “But I would visit Africa to EXPLORE the country’s music!” read a reply to posts. In a recent interview I did on NTS Radio, music historian Uchenna Ikonne discussed the reactions to his 2017 compilation of Nigerian country like Nashville in Naija. “Coming out of Nigeria these saccharine, sentimental ballads is something people don’t expect,” he said. “When people think of African music, they usually think of hot polyrhythms, not ‘nice tunes.’ Or Fela Kuti’s political fank, not Conway Twitty’s conservative crown.

This perceived inconsistency underpins the excitement many found in the video. When beliefs about culture, race, and music are entrenched, there is joy in discovering, challenging, and remixing the hidden connections between them. There was also frustration, especially among those who were already aware of this cultural association: some discussions seemed to reduce the complexity of the videos to stereotypes, such as the wonder of dancing.

The history of African country music is largely unexplored. When you put the pieces together, a long and rich musical relationship begins to emerge. It begins in the 1930s, according to writer Jesse Jarnow, and varies greatly across the continent. But in South Africa, the seed was planted by screening westerns for workers in colonial mining towns. The Singing Cowboys arrived later, their songs quickly becoming a radio staple along with Jimmie Rodgers, country music’s first star.

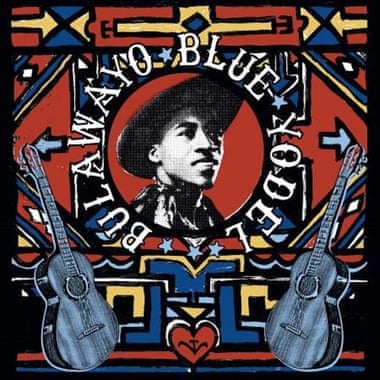

In the 1940s and 50s, when African soldiers returned from World War II and local radio stations and record labels took off, the first recordings of African country-influenced music came. Bulawayo Blue Yodel, a recent collection, compiles some of the most striking recordings of the period, providing evidence that the country has been in dialogue with African music since its commercial inception in the US. The cowboy motifs and traces of Rodgers and the Carter Family are evident in songs such as George Sibanda’s Ekhaya or the yodelling of Matthew “The Central African Cowboy” Jeffries.

There is speculation that the country was embraced because it overlapped with parts of African music – Shona music from Zimbabwe has long featured indigenous-style yodelling (throat), for example. What is clearer is that the country struck a chord in parts of Africa at a time of great social change as people moved from rural areas to towns and cities. There are parallels with the rise of the genre in the US, as ethnomusicologist Aaron Fox has said: “Country music is born when country becomes a nostalgic idea.” Stories of rural folk struggling in the city can be found in the 1950s music of Zambian singer Alick Nkhata as often as the contemporary ballads of Dusty and the Stones, from Eswatini.

But the genre also took many idiosyncratic and unpredictable turns as it made its way across the continent. Even in its early years, country mixed with local influences and developed what ethnomusicologist Tom Turino has called “new styles of common practice.” In later years, according to Uchenna Ikonne, Jim Reeves’ quiet, Christian country was seen as “cerebral” or “chin-stabbing” music. It inspired delightful, if unlikely, sounds: the disco-song of Emma Ogosi and Oby Onyioha, and the electro-funk of Willian Onyeabor. Look closely enough and you’ll find traces of the West African palm wine country of Zimbabwe revolution the musics. Many may be surprised to learn that the country has also been a vehicle for political and progressive sentiment across Africa. From pre-independence resistance music made in the mining camps of Zambia, to musicians and activists from the Ivory Coast, Jess Sah Bi and Peter One – and Ogosi donned a cowboy hat while singing Slave Drivers (Get Out).

For many people across the diaspora, the African country can feel surprising yet somehow familiar – hinting, on closer inspection, of something that’s always been there but just out of sight. There may be many black Britons of African or Caribbean descent (or, like me, both) for whom it evokes memories of a grandparent, or sheds light on the ways in which they have subtly dipped into rather than into young age.

I’ve discovered that country music runs through generations of my family—that it’s not just an American story, but a conversation between America, Africa, and Europe that echoes through time. It’s there in my father’s preference for the smooth country-rock of the Eagles or the contemplative folk of Paul Simon over the indulgent greed often associated with ’70s rock, and in SE Rogie’s palm-summer music from his home country Sierra Leone, who was inspired by Jimmie Rodgers. I can hear shades of it in my penchant for sentimental or depressing music today.

On my Jamaican side, it has seeped into the culture through love of the west, country radio, and what critic Lloyd Bradley has called the “reggaefication” of the country songbook (with sounds borrowed from Jamaica, too). But it took on additional significance for the Windrush generation. Jim Reeves and Tennessee Ernie Ford were the Sunday soundtrack for people like my grandparents who moved to the UK in the 50s. Reeves’ rich baritone is etched in all my uncles’ memories; my grandmother “played his carols every Sunday and all through Christmas.” His music resonated because of its Christian themes, but also captured a sense of cultural alienation that many in the West Indian community felt in the UK. Songs such as Across the Bridge and This World Is Not My Home ache for a home left behind or promise a better one that awaits. It’s a consistent theme, from Toots and the Maytals’ rousing cover of Take Me Home, Country Roads, to Yellowman’s dancehall classic, Jamaica Nice: “Cold London, beautiful Jamaica / country roads, take me home.”

We’re seeing more scattered but significant examples of the country’s connection to black British culture – Steve McQueen’s Small Ax film series gave the country a prominent role in the third episode, Red, White and Blue. But there are still plenty of stories worth revisiting. I often sensed my uncles’ mild resistance to the idea that the country was part of their heritage. Looking at the music of their 70s youth, country can feel very conservative, very white, compared to the post-independence Jamaican resistance songs of their 70s youth, such as 007 (Shanty Town) and Desmond Dekker. They might prefer to remember the Nat King Cole records my grandfather played rather than Reeves.

I can counter this by pointing to the country’s more rebellious manifestations in Jamaican culture. The cult classic The Harder They Come is full of spaghetti western references and with reggae legend Jimmy Cliff at the helm of the film and its soundtrack, it’s not too soon to see his persona as a singing cowboy with a twist Jamaican. Or that reggae stars known for their resistance songs, such as Toots Hibbert or Jimmy Cliff, also played with country influences. But I think it’s just as important to remember the role that Jim Reeves’s Quiet Country also played in providing a sense of hope in a hostile and inhospitable new world. When Reeves died, my Uncle Junior recalled, it was like “a death in the family. That’s how my mother wanted it.”

The history of the African country is fascinating and complex. This Twitter thread brought it into the mainstream, something more nuanced efforts have struggled to do. Social media has a way of showing the tensions and complications of a story like this with a fleeting immediacy. But it can also condense them in ways that take away the richness and experiences of the people who live with the music. In a world mediated by social media that makes uprooted connections travel fast, I yearn for one that can give space to the subtle reality of musical expression and its cultural resonances, rather than reduce them to startling images.