Was La Malinche a traitor to her people or a survivor of her circumstances? Icon and cultural hero or victim? These are the questions the San Antonio Museum of Art’s latest exhibit seeks to address.

On show Oct. 14-Jan. 8, 2023, Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche uses more than 60 works of art to examine the history and legacy of the indigenous Nahua girl who was enslaved in the 16th century.

“This is groundbreaking,” says Emily Ballew Neff, Ph.D. and Kelso director of the museum. “We use this word very carefully. This is the first comprehensive presentation of La Malinche.”

The exhibit, which was organized by the Denver Art Museum, opens with a video introducing Malinche. Born sometime between 1500 and 1505 near the Gulf of Mexico, she lived a short but influential life, dying in 1527 or 1528, says Lucía Abramovich Sánchez, the museum’s curator of Latin American art. As a young girl, she was sold or kidnapped into slavery and then in 1519 was given as a slave to Hernán Cortes when he conquered the Mayan city where she was held. She became an interpreter for Cortes as well as a mistress, bearing his first son.

While Malinche left no written accounts of her experiences, this has not stopped people from interpreting her story through their own political, social and cultural agendas. In the exhibition, guests will see works by nearly 40 artists who created pieces addressing Malinçe between the 16th century and today.

“La Malinche and her story have permeated Mexican and Mexican-American popular history and culture for hundreds of years—for better or worse,” says Abramovich Sánchez.

Along with the video, visitors to SAMA are greeted with a map that was commissioned for the exhibition. Created by LA-based artist Sandy Rodriguez, the piece relates Malinche and other Mayan women’s experience of being handed over to the Spanish with the death or disappearance of 19 indigenous women in recent years.

“It brings us up to the present day on these issues that deeply affect indigenous women,” says Abramovich Sánchez.

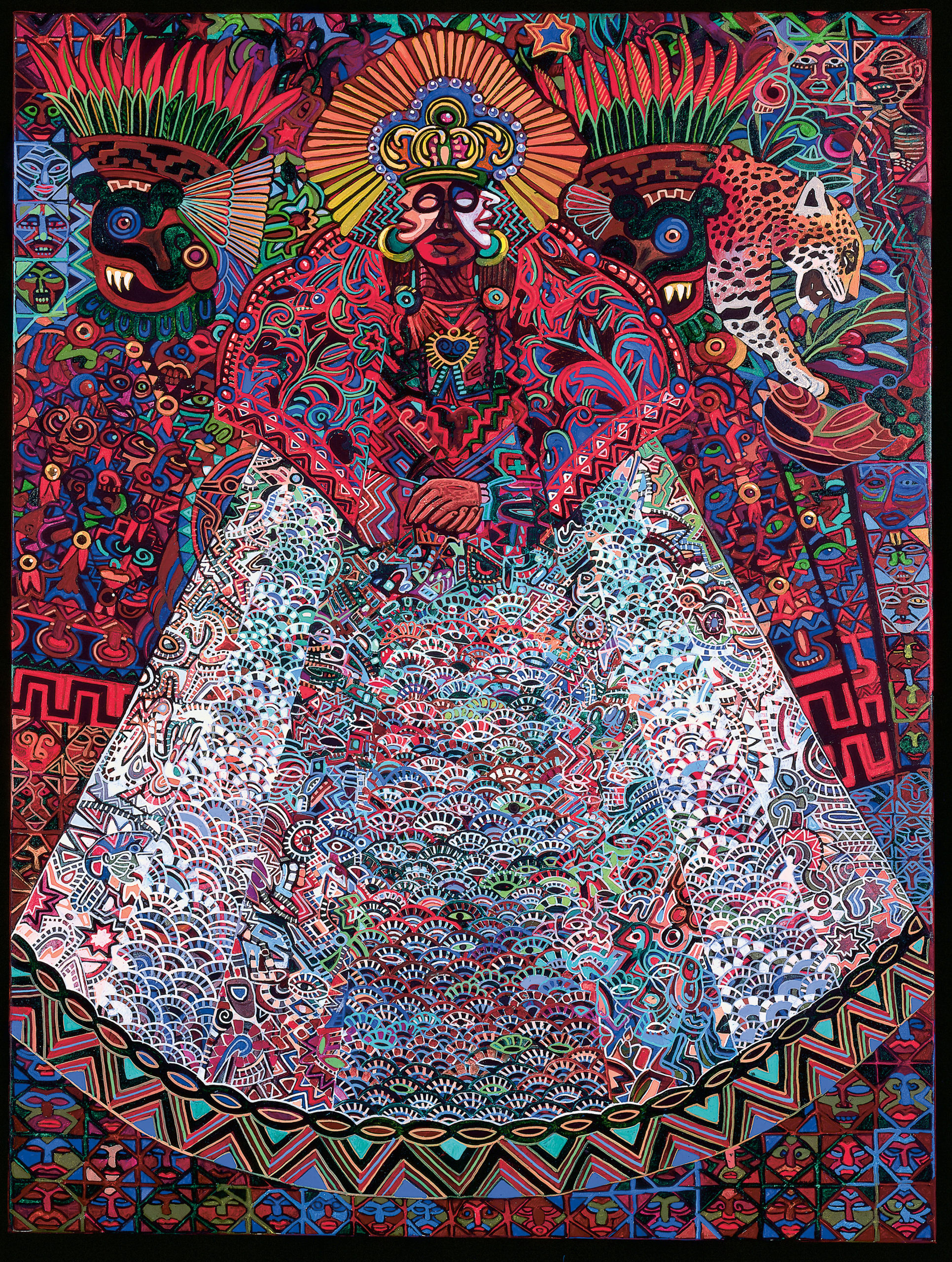

Within the galleries, the exhibition is divided into five themes: La Lengua/The Interpreter, La Indígena/The Indigenous Woman, La Madre del Mestizaje/Mother of a Mixed Race, La Traidora/The Traitor and Chicana/Contemporary Bolifications.

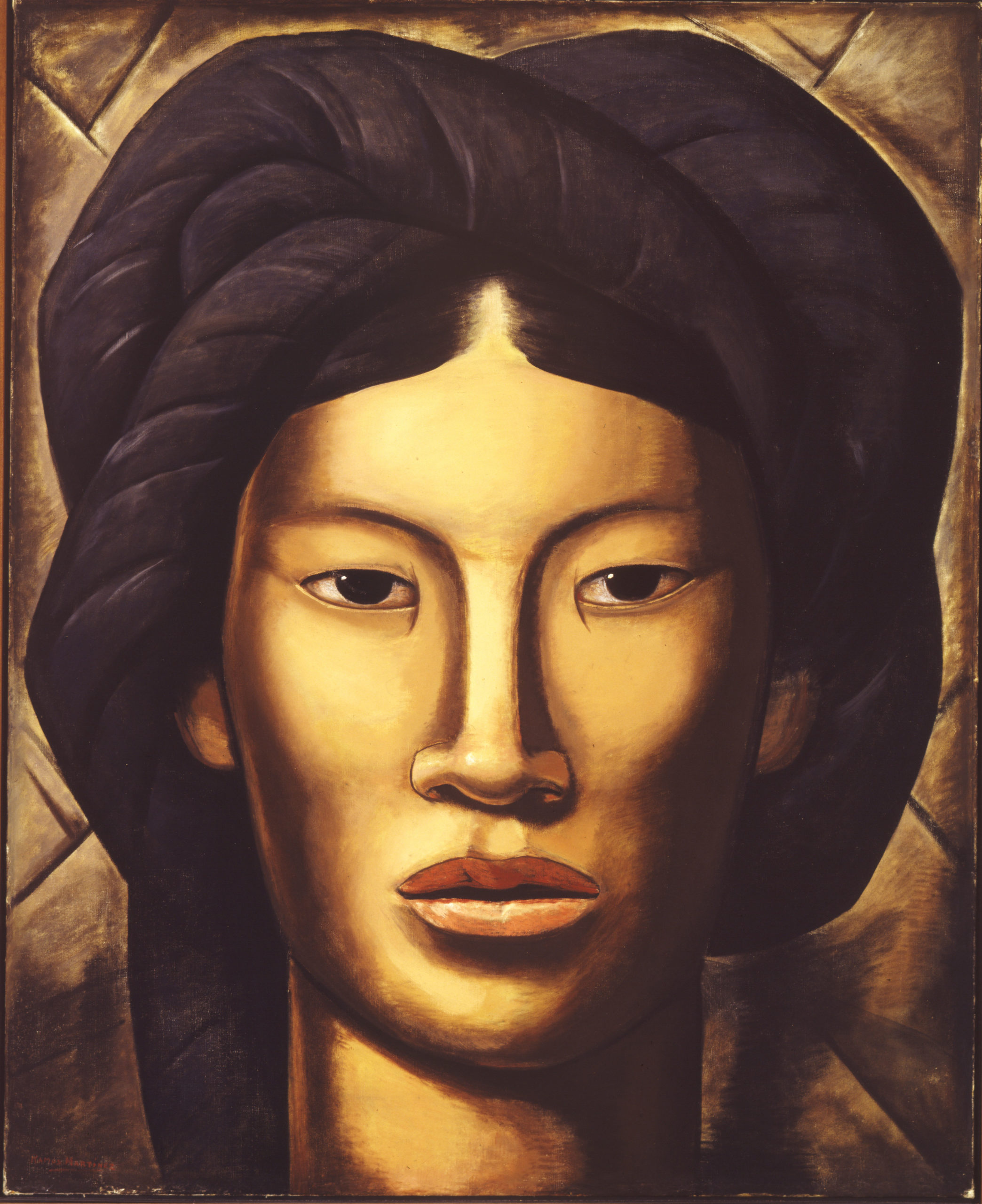

In the second section, look for the large 1941 oil painting “La Malinche” by Jesús Helguera. The work is a large-scale depiction of some of his calendar paintings, which were popular in Mexico at the time. The piece shows a light-skinned Malinche, which is how indigenous women were often depicted in Mexican pop culture at the time. Nearby, a 1940 oil painting by Alfredo Ramos Martínez pays more attention to Malinche’s indigenous roots, both through her hair and coloring.

In the third section, “La pareja (the couple),” by Jorge González Camarena shows Malinche and Cortes in more equal positions, depicting them as a power couple, although Cortes is still clearly in control.

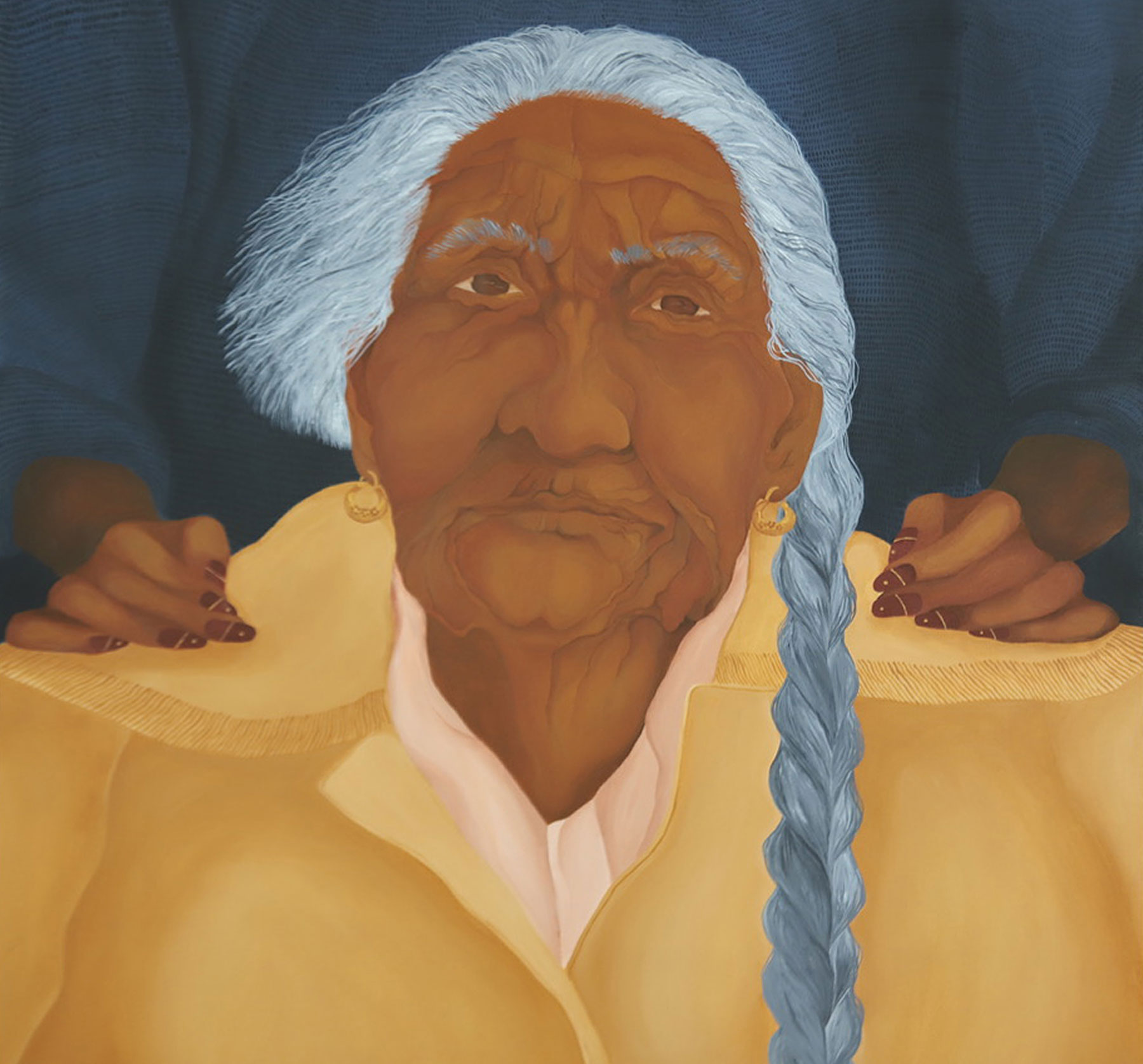

The final section shows how Chicana artists have reclaimed Malinche history in recent decades. Instead of portraying her negatively as a traitor, they show a woman who did what she had to do to survive despite being enslaved. In a 1994 painting by Gloria Osuna Pérez, Malinche is depicted as the oldest woman who never became. It is based on the day when the artist’s grandmother had to cut her hair because she could no longer braid it herself – the grandmother’s and Malinche’s braid was an important part of their identity.

Although hosted in Denver, the expo has San Antonio ties. Visitors will find a poem by the city’s inaugural poet, Carmen Tafolla, as well as pieces by local artists Felipe Reyes and Cesar Martinez.

“Malinche did many, many things in her short life – it was a short life because of her circumstances,” says Abramovich Sánchez.

See Exhibit

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche

October 14 – January. 8

San Antonio Museum of Art, 200 W. Jones Ave.

Guided gallery tours are available from noon to 1pm on Sundays and from 5.30pm to 6.30pm on Tuesdays

Special events

October 16: Family Day Hispanic Heritage Celebration

October 25: The artist’s conversation with Santa Barraza

October 25-November. 6: Ofrenda: A Legacy of Women

Nov. 18: Guadalupe Dance Co. will perform a piece inspired by the exhibit at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center.

Through Jan. 8: Mixtli offers menu and bar items inspired by the exhibit.